Years ago I was in an online conversation with a person who was critical of studying historical swordplay (vs. just picking up a practice sword and making it up), when he wrote that the manuals were pointless “because I can beat every one of the plays.” I don’t know if I was successful in getting across to him that he was missing the point of what the plays were for.

I have also seen people who were so transfixed with each play in a manual that they had arguments over minute details, such as whether your foot should be pointing 20 degrees when you step or 30. Similarly, I’ve seen others who were treating the manuals like dance instructions - You step here with your right foot, and raise your hand like so and VIOLA! You win! I believe those people also are missing the point.

So here in this short posting I want to just go over my view of how to use the plays in a manual to learn and improve.

The lessons of the plates/plays

The various authors designed plays to illustrate (both figuratively and sometimes literally) the lessons they were trying to get across. They are contrived situations meant to show tactical choices and potential consequences of those choices. This means that they are drills.

As I’ve written before, the difference between each play is a difference in the players’ choices - either which posture to assume, which side to attack, or what to target, for instance. And each play has at least one distinct lesson to impart, and often more than one. But they are created to illustrate and reinforce lessons - not to show that if you do exactly *these* things in a fight, you will win.

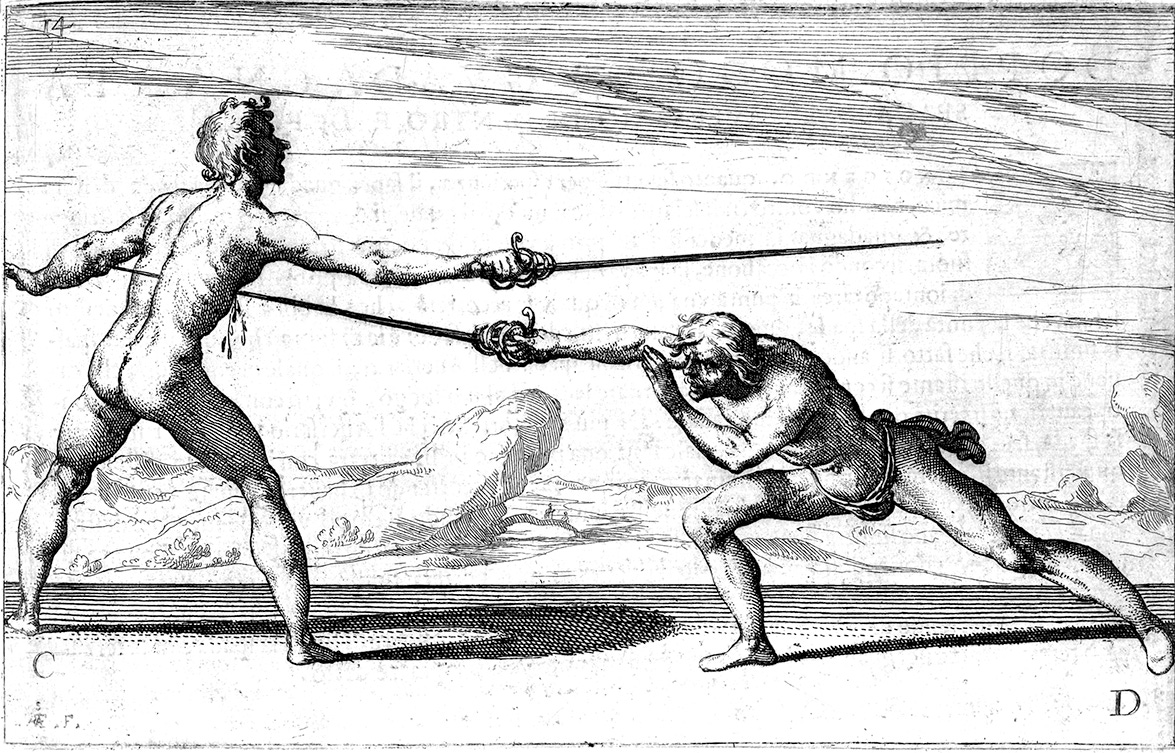

Capoferro’s plate 7, for instance, introduces the process used throughout the manual - 1) enter measure and stringer, which triggers 2) a cavatione, which is then 3) countered. It also introduces the concept of using a smaller action to counter a large one. Or, if you wish, a faster action to counter a slower one. And along with that is applying the technique that makes it so that your opponent HAS to choose a larger/slower movement - the stringere.

Plate 8 reinforces lessons from plate 7 (the 1-2-3 process and forcing your opponent to make a big movement) and introduces new distinct lessons for consideration and practice, including giving you the opportunity to practice a larger tempo than plate 7. In plate 7 you simply turn your wrist. In plate 8 you move the entire leg. So it reinforces lessons and adds a new complication - needing to move an entire leg - while also giving you a play in which by necessity you’ll practice knowing when your opponent is going for your leg.

Plate 9 then again reinforces the same things from 7, and adds an even bigger tempo - moving the entire body forward into grappling range.

And note that in Capoferro, the first set of plates (7-14) all start by gaining the opponent’s blade on the inside. Plate 15 then describes the method of gaining and attack on both the inside and outside (which arguably should have been an earlier lesson).

Plate 16 then starts all the outside plays by demonstrating the same concepts as plate 7, but with an initial approach from the opposite side of the opponent’s sword, and thus some different mechanics to consider. For instance I find that gaining the opponent’s sword and thrusting from the outside is more natural feeling than gaining and thrusting from the inside. There are different mechanics involved in a thrust in opposition in 4th from a thrust in opposition in 2nd. So that tells me I need to practice landing my inside thrust in order to make it feel as natural as the outside.

And since everything is context-driven, you yourself may get something from practicing a play from a manual that I didn’t. And that’s great. As my Shihan in Shotokan once said, when you reach a higher level of training, you should go back to the earlier kata/drills and find the things that you missed the first time you learned them. As your knowledge has expanded and your context has changed, you will bring different eyes to the tactical choices in each kata.

Tactical lessons are not precise dance steps

When I’m approaching my opponent, gaining their blade, and attacking in opposition, my actual motions will be dictated by the height, reach, and athleticism of my opponent. So my precise movements will vary depending on whom I am fencing.

This means that I can successfully implement one of the plays with my hand higher in one instance than in another, and my lunge longer against one opponent than another. The important parts are the actions that put proper fundamentals into play. Controlling my measure against an opponent, using good blade work to trigger a tempo that I then use to my advantage. I want to work not toward an ideal form, but be able to work against a variety of opponents.

In an exchange what will matter is that I used the tactics to force my opponent to go where I wanted them and then was able to counter it. What doesn’t matter is my hand being 2 inches lower than what’s illustrated in the manual. If I dominated their blade on the attack, then I did it right.

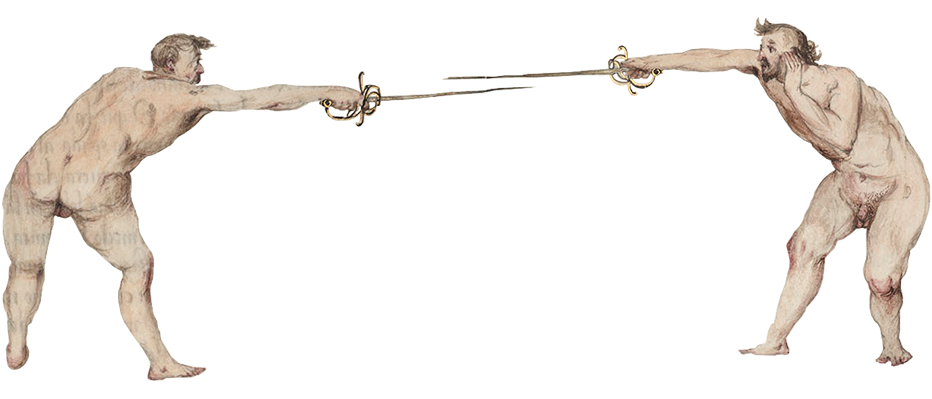

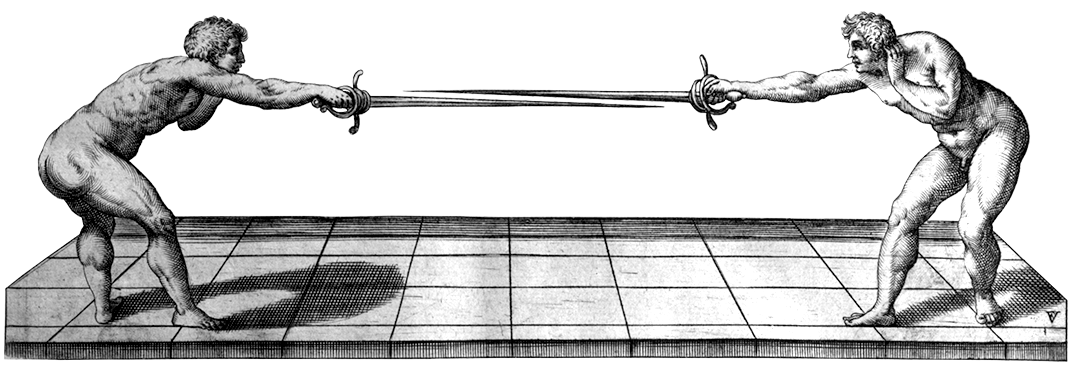

For instance, let’s look at the differences in Fabris’ 1601 treatise and his 1606 manual:

Both of the players in these illustrations are in a “better terza.” Yet look at the differences in their feet, the height of their arms, the turn of the shoulders/torso, etc. Fabris claims that the images in both are correct. So again - variations are acceptable and even expected.

How to use the plays

You take these drills and work through them with various partners to see the dynamics, and adapt when they change. You work with the partners to make sure you’re actually controlling the dynamics and they’re not just giving you the “right” response. (NOTE: it’s often difficult to be sure of this until you’re working on initiating plays during sparring/free fighting bouts.)

You then increase the speed of the drills, reinforcing that the actions and responses flow. Then you can either start varying the plays in non-standard ways, or similarly you can give the opponent options of 2-3 plays and you have to either be ready for them all, or you can try to make them apply the one you want.

Once you can walk on a tournament field and make your opponent choose the actions you want them to, and you adapt when the context is off, you’ve then already started expanding beyond the plays.

Expanding beyond the plays

The way I teach, learning the plays is the intermediate part of learning swordplay. The plays introduce and reinforce the main tactical choices in a system. When you’ve worked through many of the plays and internalized the lessons to be found, you should be able to start making up your own tactical situations and design choices and responses that make sense. In other words, a relatively advanced student can create their own plays on the fly in order to teach or reinforce lessons.

This usually signals that you’re able to control your opponent and set up a puzzle that you are prepared to solve in a sparring match. You have by this time usually learned to evaluate the situation in front of you and quickly play through the options, and make a plan before stepping in.

But even then, as my Shihan said, it’s always good to go back and look through the plays again. There’s often still more to learn.

Conclusion

If there’s a takeaway, it would be that the plays/plates from the fencing manuals are there to illustrate lessons the author wanted to get across - not to dictate exactly what happens in a fight and/or how precisely to move. No play demonstrates a perfect unbeatable action - they all can be countered. They are drills meant for training. And in the end, the tactics drive and are driven by the three fundamentals - measure, tempo, and the use of the weapon. If you use the plays to reinforce how to apply those fundamentals well, then you’re probably doing it right.

So I hope this is clarifying for some. I’m sure it’s old news to others here, but it’s always worth reiterating. Also - it looks as though I may be sending these releases out on Thursdays for a while going forward instead of my traditional Tuesday mornings. So hopefully you’ll find them in your inboxes on Thursday mornings until I find a new routine. (or maybe that IS the new routine?)

Be safe and fence well!