Gaining the opponent’s blade - part 1

It is of no small profit nor of little beauty to know how to gain the sword of the adversary in all the guards.1

In his 1610 book on swordplay, Ridolfo Capoferro refers to gaining and “stringering” an opponent’s sword.2 Nicoletto Giganti advises you should be “resting your sword on [your opponent’s]” in his 1606 book.3 Salvatore Fabris writes about “finding the sword” where your “opponent cannot wound you without passing through your forte.” He adds: “And your forte is so close to his point that the latter is ‘found’ in the tempo that the opponent uses when he moves for the lunge.”4

What they’re talking about is a way to keep yourself safe from and constrain, or control, your opponent’s sword while in fighting range, or while closing distance. This is a concept that is key to understanding and employing the northern Italian rapier system. I do not exaggerate when I say that nearly 100% of my own fights include, and in fact are driven by, the concept of gaining the opponent’s blade.

There’s some nuance to this, and I want to make sure that I get it all across well. This is very simple to do, but also misunderstood by some, and I want you to understand a lot of the whys and details here right off the bat so that you’ll be doing it right when you practice it.

NOTE: I also made two videos on this subject, in case you learn and process better through that medium.

***All of the quotes from the Vienna Anonymous manuscript in this issue are from Tom Leoni’s translation.

***All of the quotes from Ridolfo Capoferro’s book in this issue are from the Swanger-Wilson translation.

***All of the quotes from Salvatore Fabris’ books in this issue are from Tom Leoni’s translation, or A.F. Johnson’s.

***All of the quotes from Nicoletto Giganti’s book in this issue are from Jeff Vansteenkiste’s translation of a 1606 printing.

The parts of the sword

First, let’s go over the parts of the sword most relevant to this discussion.

Forte (FOR-teh): The forte, or “strong” of the blade is the ½ or so nearest the hilt. It is the part used for defence and for blocking attacks. Therefore it doesn’t need to be sharp, and often wasn’t.

Debole (DEH-bo-leh): The ½ or so of the blade that includes the tip is called the debole - or literally “weak.” This is the dangerous sharpened part that also, because of the mechanics of leverage, is the part your opponent can use to control you.

True edge: The true edge is the edge of the blade you hit with when you cut with a downward stroke of the sword. When you hold the sword in a normal grip at your side, the true edge is toward the ground.

False edge: The opposite edge from the true edge. When you hold the sword in a normal grip at your side, the false edge is toward the sky.

Ricasso: The part of the blade that disappears into the quillon block, and is protected by the hilt, is the ricasso. This is the part of the blade you will wrap your finger around when holding the rapier in this system.

Divisions of the blade - or “degrees of strength”

It’s also extremely useful to understand how several authors have divided the blade into sections.

Renaissance and Baroque authors would describe the blade as being divided into two or more sections. Capoferro thought it best to imagine the blade divided into two sections.5 Giganti similarly references only the forte and debole.6 And Fabris divides the blade into four.7

A Spanish author, Jerónimo Sánchez de Carranza, divided the blade into nine sections he refers to as the “degrees of strength.”8

These divisions will be useful in later parts of this discussion, so understand that the debole contains sections 1, 2, 3, and 4, and the forte is broken into 5, 6, 7, and 8. Section 9 is the ricasso - the part directly against the quillons, or cross guard, that you wrap your finger around. Section 1 - containing the point - is the weakest but most dangerous part of the blade, and section 8 is strongest and closest to your hilt.

So what is the gain?

To gain the opponent’s blade really means to acquire, or control it,9 even if for a brief time - which is really all we can ever expect in a fencing exchange.

The northern Italian authors used different terminology to name the same concept. For Fabris, when a sword is gained it is “found.”10 Capoferro substitutes the term “stringere” when he’s writing about gaining the blade.11 For Giganti, gaining the sword is “binding” it.12

In all cases, when you successfully gain an opponent’s blade, you are using some combination of the parts of your sword, usually gravity, and the angling of your bodies, swords and/or arms to gain strength or mechanical advantage over their sword.

How to do it

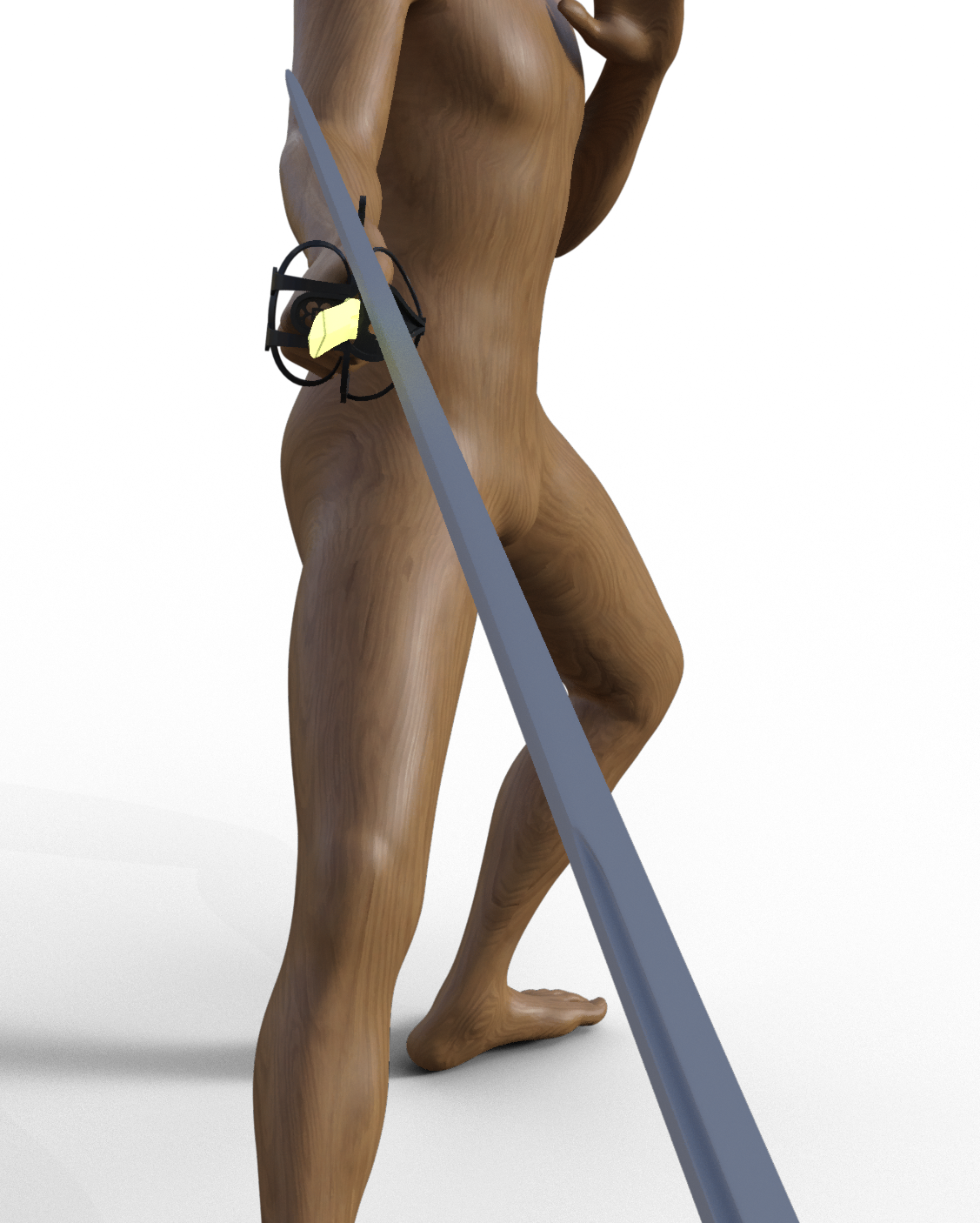

To gain an opponent’s blade, you want to place a greater length of your blade over a lesser length of theirs.13 And you want to turn your true edge - the edge you would usually try to cut someone with - toward their blade, and aim your point at their silhouette or just past it.

A former owner of a copy of Giganti’s first book wrote this extra detail in the margins:

Then consider the enemy’s guard, and approach little by little with the sword binding him, that is, placing yourself in order to secure yourself from his sword, which is done by resting your sword over his, by holding your thumb in the hilt over the spine of his sword, that so, you will be able to press better over that of the enemy so that he cannot throw a blow if he does not disengage, and disengaging he makes two tempi, then gives you tempo to wound him if you are quick to throw while he is delayed in the disengage,14

Shutting out the sword

The author of the Vienna Anonymous considered the gain as “shutting out the opponent’s sword.”15 They further explained:

To gain the opponent’s sword is to place yours on his debole so that yours is stronger than his while it is in presence. This way you can push away his, but he cannot push away yours; or, if he wishes to push it away, he must move his point out of presence.16

Look back to the divisions of the sword I illustrated earlier. When your swords cross, you want a number from your sword to be over a lower number on theirs. You want your 3 over their 1; your 4 over their 2; etc.

Do not touch

Capoferro’s and Fabris’ recommendation was to not touch the opponent’s blade when you gain.17 Giganti advised to only “barely” touch it.18 But realize that any time you touch your blade to theirs you are giving them information about your intentions.

To be clear, you might sometimes want to touch blades and convey that information. But I don’t recommend it unless you have a clear reason for doing so.

Getting them in the “pocket”

I also teach that the true edge of your blade and your bottom quillon form an “L”, or a triangular pocket, that you want to get your opponent’s sword into. This can help with the visualization that ensures your true edge is always aiming at the opponent’s blade.

You can lay your 5 over their 3, as in the above image, but if you don’t get their blade in that “pocket” your position isn’t a strong one.

In this image above, I have rotated my sword so that my bottom quillon is toward their blade, putting him in the “pocket” and creating a strong gain.

To be continued…

In Part 2 of our discussion about the gain, we’ll look at what it means to be “in presence,” we’ll discuss the three types of gain as laid out in the Vienna Anonymous, and we’ll condense all that you’ve learned about how to accomplish the gain to four instructions, or admonitions.

In part 3, I’ll explain the ‘whys’ behind the gain. Why should we do it? What’s the tactical use and advantage of gaining the opponent’s blade. (Yes, yes, you’ve already seen a bit of that in the quotes above, but we’ll dig a little deeper.)

Next up:

Northern Italian Postures, Part 4: The postures of Nicoletto Giganti (Paid subscribers)

Gaining the opponent’s blade - part 2 (All subscribers)

Ridolfo Capoferro. 1610. Gran Simulacro Dell’arte E Dell’uso Della Scherma. Translated by Jerek Swanger and William Wilson. Page 32.

For instance, Ibid. Cap. XI, Page 22. (“it is only necessary that I stringer the debole of my enemy’s sword in a straight line, with the forte of mine, and this straddling it without touching,”)

Giganti, Nicoletto. 1606. Scola, Overo Teatro. Guards and Counterguards, Page 15. Translated by Jeff Vansteenkiste. (“Afterwards approach him little by little with your sword binding his for safety, that is, almost resting your sword on his so that it covers it because he will not be able to wound if he does not disengage the sword.”)

Fabris, Salvator. 1606. De Lo Schermo Overo Scienza D’arme. Cap. 9, Page 11. Translated by Tom Leoni.

Ridolfo Capoferro. 1610. Gran Simulacro Dell’arte E Dell’uso Della Scherma. Translated by Jerek Swanger and William Wilson. Of the Sword, Page 35. (“In the sword are to be considered the forte, the debole, the false edge, and the true edge.”)

Giganti does not explicitly describe the sword as divided into two sections, but throughout his book he refers to only two parts: the debole and the forte.

Fabris, Salvator. 1606. De Lo Schermo Overo Scienza D’arme. Divisions of the Sword, Page 2. Translated by Tom Leoni. (“The blade of the sword is divided into four sections.”)

Jerónimo de CARRANZA. 1612. Compendio de La Filosofia Y Destreza de Las Armas, de Geronimo de Carrança. Por Don Luis Pacheco de Naruaez, Etc.

See Florio, John. 1611. Queen Anna’s New World of Words, Or, Dictionarie of the Italian and English Tongues. (“Guadagnare: To gaine, to winne, to profit, to get, to acquire.”)

Fabris, Salvator. 1606. De Lo Schermo Overo Scienza D’arme. Cap. 9, Page 11. Translated by Tom Leoni. (“Finding the sword means occupying it.”)

Ridolfo Capoferro. 1610. Gran Simulacro Dell’arte E Dell’uso Della Scherma. Page 30. Translation by David Biggs. (“& you must also know, that we intend to stringer the sword, as well as (as much as) to gain it.”)

Giganti, Nicoletto. 1606. Scola, Overo Teatro. Guards and Counterguards, Page 15. Translated by Jeff Vansteenkiste. (“Afterwards approach him little by little with your sword binding his for safety, that is, almost resting your sword on his so that it covers it because he will not be able to wound if he does not disengage the sword. The reason for this is that in disengaging he performs two actions. First he disengages, which is the first tempo, then wounding, which is the second.”)

Fabris, Salvator. 1606. De Lo Schermo Overo Scienza D’arme. Cap. 9, Page 11. Translated by Tom Leoni. (“Here is something that may help with this concept. If you are in guard, and wish to find the opponent’s sword, you should situate your point against his so that the fourth part of your blade is into the opponent's fourth part, but with a greater portion of yours into his.”); Also: (“You should consider your opponent’s sword “found” when your own is situated so as to be stronger than his and cannot be pushed away but, rather, can easily push away that of the opponent.”)

Giganti, Nicoletto. 1606. Scola, Overo Teatro. Found on page 104 of the translation by Jeff Vansteenkiste.

Leoni, Tom. 2019. Vienna Anonymous on Fencing: A Rapier Masterclass from the 17th Century. Lulu.com. Page 14.

Ibid. Page 15.

Ridolfo Capoferro. 1610. Gran Simulacro Dell’arte E Dell’uso Della Scherma. Translated by Jerek Swanger and William Wilson. Cap. 11, Page 25. (“it is only necessary that I stringer the debole of my enemy’s sword in a straight line, with the forte of mine, and this straddling it without touching,”); Fabris, Salvator. 1606. De Lo Schermo Overo Scienza D’arme. Cap. 4, Page 3. Translated by Tom Leoni. (“Forming a good counter-posture means situating the body and the sword in such a way that, without touching the opponent's blade, the straight Line between the opponent's point and your body is completely defended.”)

Giganti, Nicoletto. 1606. Scola, Overo Teatro. Guards and Counterguards, Page 26. Translated by Jeff Vansteenkiste. (“From this figure you learn that if your enemy is in a guard with the sword on the left side, high or low, you approach him to bind him outside of his sword outside of measure, with your sword over his so that it barely touches it”)