When I’m asked to coach fencers, or when I’m asked for advice on how to be more successful in a bout, the large majority of the time I start by correcting their use/application of measure. It’s the thing that is done wrong more often than any other thing, and if you’re not using measure well, then it makes most other techniques that you can practice and improve markedly harder to pull off. If you’re using measure well, everything else becomes easier and makes more sense.

And in the large majority of historical fencing matches I’ve watched - in person or on video - the fencers aren’t mentally engaged until they are much too close.

So here I want to go through what I see happening when people fence, and maybe talk a little about why I think it might be happening.

Measure

If needed, go back and review my lessons on measure. But here’s an overview:

Controlling how close you are and when to get closer is vital in a fight. You cannot strike your opponent if you are out of the measure needed for your weapon and for your planned attack. But also, for rapier combat, there are a few different measures to take note of and different ways of considering them.1

Let’s break down the four measures as I teach them based on the primary historical manuals I study:

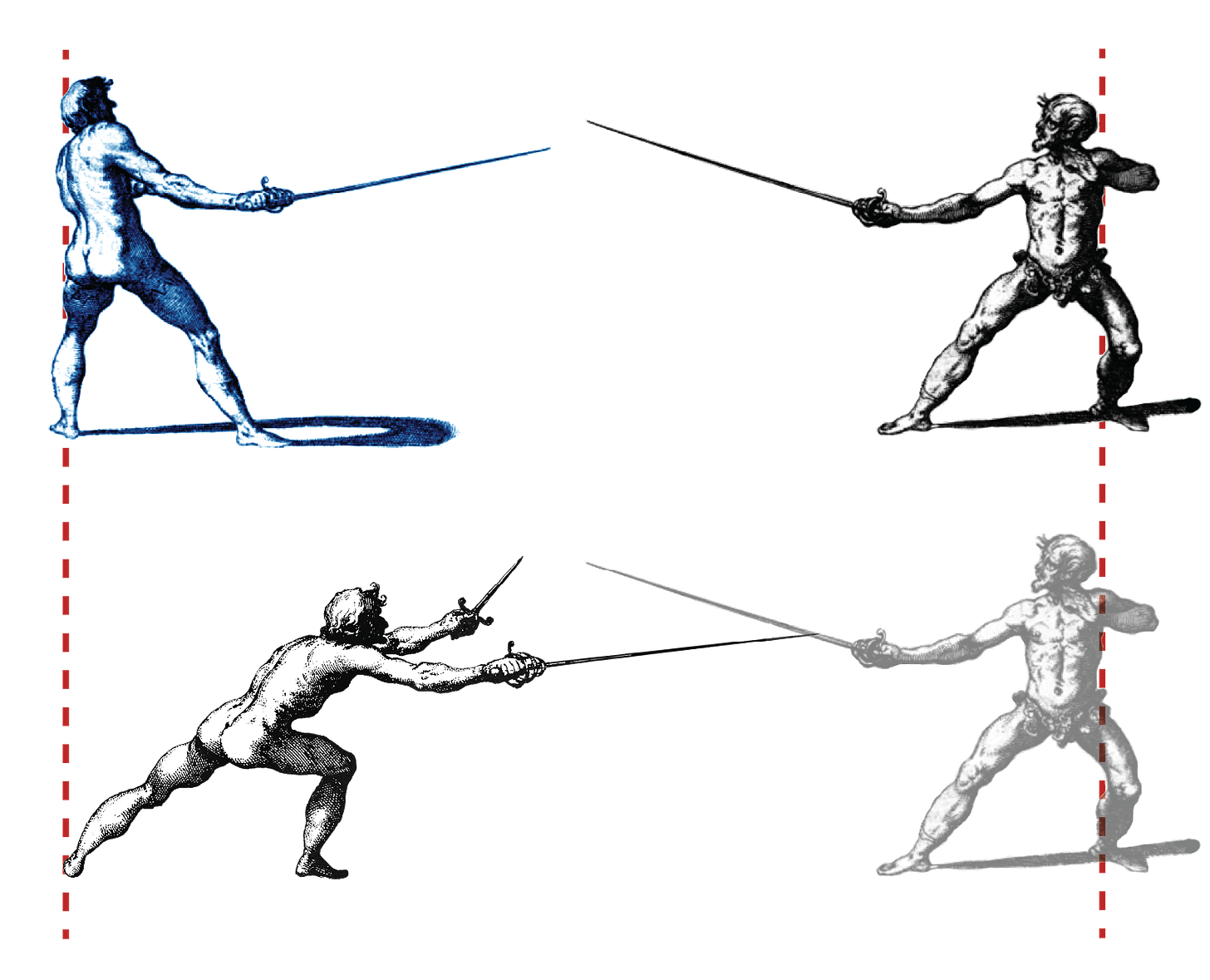

Out of Measure: You are out of measure when you can’t reach your opponent even with a long pass or dynamic lunge. You can’t reach your opponent but also, they can’t reach you. This is the place to think about or plan the fight and consider your options. Also you don’t need to remain in posture when you’re out of measure - you shouldn’t need to focus as much on your protection (though some fighters will use this opportunity to run at you, so you should at least be aware enough of your surroundings to protect against that possibility). (Note in the image below the tips of the extended swords have not crossed and neither can reach the other with a dynamic lunge)

Large or Wide Measure: You can reach/stab your opponent with a stepping (dynamic) lunge or a long passing step. When you’ve entered into a measure where you can *just* strike your opponent by lunging with a step, you’re at wide measure. Recall what Capoferro wrote: “The wide measure is, when with the increase of the right foot, I can strike the adversary.” Fabris, Capoferro, and the Vienna Anonymous recognize wide/large/larga measure. For Giganti, though, at this point you’re simply in measure and the rest isn’t delineated. (Note in the image below the tips of the extended swords have now crossed, and at least one of them can reach the other with a dynamic lunge)

Narrow Measure: When you can strike your opponent with a firm-footed lunge - e.g. lunging without taking a step - you are at narrow measure. Again, Capoferro: “The fixed foot narrow measure is that in which, by only pushing my body and legs forward, I can strike the adversary.” Fabris, Capoferro, and the Vienna Anonymous recognize narrow, or stretta measure. (Note in the image below the extended swords have now crossed well into the debole, and at least one of them can pierce the other halfway through with a dynamic lunge)

Narrowest or Close Measure: When you can strike your target without even bending a knee, you are at close measure. When you can just reach out, or maybe lean into an offensive posture, and strike your target, you are at the narrowest measure to it. Capoferro even describes stepping back to strike when your opponent is attacking: “The narrowest measure is when the adversary strikes at wide measure, and I can strike him in his advanced and uncovered arm.” Capoferro is the only one of the four to call out this measure. (Note in the image below the extended swords have now crossed at or even past the midpoints, and at least one of them can pierce the other all the way through with a dynamic lunge)

HEMA and SCA sparring

In the large majority of HEMA and SCA sparring I see, both on video and in person, the opponents start the engagement in narrow measure and often stay there until one or both of the fencers is hit. The image below shows narrow measure in different postures. You’ll note the feet are in the same places, but the position of the swords may give the illusion of more distance.

It’s easier, in my opinion, to judge roughly what measure you are in when you and your opponent are both fencing with your sword arms extended. It’s a simple thing when you’re both extended to use the general rule that once your tips cross you are getting close to or already in wide measure, as you can see from the sequence of images in the descriptions of the four measures, above.

Compare, though, what wide measure looks like when your sword is extended, and when it’s not extended, below.

It often looks, and feels, like you’re farther away when you and/or your opponent pull your swords back. Yet this is still where your fight should really start in earnest. This is where you begin to be in danger. At this distance you want to have already begun defining the space between you, and dictating your opponent’s choices, no matter how you or your opponent are holding your swords.

Extending the sword arm

If I want to approach my opponent and start dictating the fight using Northern Italian tactics, with rare exceptions I want to keep my sword arm extended, with my elbow somewhere out in front of - not beside - my torso. Holding your sword extended toward your opponent literally keeps them further away from you, giving you more space and time to react.

A personal note - I don’t consider your sword or sword arm extended when the upper arm or bicep is perpendicular to the ground. In the picture below, the fencer on the right has their sword extended (I mean, duh). The one on the left does not. The fencer on the left is, to me, closer to a “sword refused” posture.

Here are three examples from Capoferro’s, Fabris’, and Giganti’s manuals. Note the bicep may not be parallel to the ground, but it’s not perpendicular either. There is space between the ribcage and the elbow.

Don’t throw away your tactics

In any case, you need to realize that even if you prefer fighting in more of a sword-refused style, when you move into narrow measure before fully getting into fight mindset, you’ve effectively thrown some of your best tools out the window and walked into essentially a game that relies more on speed. You’ve started the chess match with several pieces already scattered on the board and some of them already captured.

And to be clear - some people like that game! It’s fast and exciting! But you need to be aware that that’s what’s happened. If you find that when the fight begins you don’t seem to have time to make a plan and force your opponent into a disadvantageous position before getting hit yourself, then that likely means you’re wandering in too close before mentally “starting” the fight. You’re walking into narrow measure before mentally engaging.

Why do we start too close?

Some people like to fence at close range. Others don’t realize they’re doing it, or they don’t know that they’re losing a lot of tactical choices when they do it.

One reason I believe people start too close is that most fencers do not extend the sword. They fight with a “sword refused” style as I described above, which means they have to get closer in order to engage the blades and “feel” like they’re in a sword fight. Indeed - some fencers pull their sword back IN ORDER to draw their opponent in closer! (Hint - they are the ones who know they’re doing it and who enjoy that kind of fight!)

And as you can see below, when you and/or your opponent pull the sword back, it’s less obvious that you’re in range unless you have developed your sense of measure based on the opponent’s body and/or feet. These two below have entered into wide measure, even if they don’t “feel” like they’re in fighting range.

I argue that this “feeling” of being in a sword fight as we *think* they should be - thanks to growing up watching movies - is what is driving most fencers. Most fencers, whether they know it or not, are trying to experience that action and intensity that they have been taught by Hollywood that a swordfight should feel like. And especially when they’ve been learning to fence through sparring, or through disconnected lessons and actions, they approach the fight wanting to “mix it up” and “go at it” with the opponent. They don’t have the training to evaluate the fight well out of range and start defining the fight as they enter wide measure.

In the end, when fencers close into narrow measure before they start the fight, it’s no longer a tactical chess game for most - it’s really more of a brawl, with all the adrenaline and excitement that comes with it. Which again - that can be a lot of fun! But don’t mistake it for a good application of a renaissance rapier system.

If you want to stop getting hit before you have time to start controlling the fight and using your techniques, it’s almost certainly because you are starting off too close.

Drilling measure

You can drill your measure as you practice your attacks and lunges. I often use a tree or other object with some visual mass when I’m reinforcing my measure training. (When I’m working more on precision and targeting, I use something smaller)

Go back and study what the authors said about measure, and what I teach as a distilled explanation above, and work primarily on:

knowing when you are out of measure

the transition into wide measure - where you can just reach your target with a stepping lunge

the transition from wide to narrow measure

knowing without conscious thought that you have arrived in narrow measure - e.g. “too close to only now be starting the fight!” (for me, when I start too close alarm bells go off and something feels ‘wrong’)

And finally, I’m often asked “but how do I stop them from getting too close to me? They just keep walking into my measure!” My somewhat glib, but absolutely honest, answer is - you hit them. You punish them for walking unprotected into your measure. And to do that, you have to be aware of your measure, and be ready and protected yourself when it happens.

Conclusion

Once you read through this article, go watch some videos of HEMA and SCA tournaments and sparring. Watch the two opponents approach one another, then freeze the video when you feel they “started” the fight.

You will usually see that moment when they come to full defensive attention. That instant when you feel like the two really engaged and came to full alert and the fight was “on”. Often one of them will stop, even if briefly. And when you pause the video, note that usually they have already stepped into narrow measure.

And as I’ve written - by the time you’re in narrow measure, a good chunk of your tactics are no longer very effective. If you haven’t set up the space between you and your opponent and manipulated your way into narrow measure - if you just wandered in and then set up in “go” mode - then the fight becomes as much about your twitch reactions and speed as it does anything else. This is what I mean when I talk about a fencing match devolving into a gun fight. At that point, if you haven’t tactically worked your way into that measure, the fastest and smoothest fencer will usually win.

Next up:

Things to do when your sword is constrained - part 2 (Paid subscribers)

Product review - Balefire Blades (All subscribers)

This is really really helpful. I do wander even into wide measure without thinking I'm there yet, and get hit by what I thought was "a shot from nowhere" but only because I wasn't mentally prepared yet.

Do you recommend people use the same weapon when learning measure, to remove a variable, or do you recommend changing between ones with different blade lengths, so as not to get used to a particular piece?

I know that rapiers are supposed to have an ideal length accounting for the size of the fencer, so maybe this question is more relevant for sideswords. I'm asking because I found myself missing a cut by an inch when I cycle through my sideswords, and I wonder if I should stop doing that and stick to a piece.