The lunge and its mechanics - part 1

The lunge is the primary attack in the Northern Italian thrust-fencing system. At its basic, a lunge is just “a quick thrust or jab (as of a sword) usually made by leaning or striding forward.”1 But like all of the other core postures and actions, it’s important to get the mechanics correct to form a strong and nimble lunge,2 and to avoid future injury.

In this 3-part series, I’m going to show you the lunge as it’s taught by the Tattershall School of Defense. We’ll go through the whole sequence a piece at a time, and I’ll point out a few details to know that make this lunge what it is. This will mostly cover the WHAT to do and HOW to do it. The WHY gets into tactics - I’ll write a future post on that. This series can also be considered a companion to the video series I put out on the subject on my Youtube channel here.

***All of the quotes from the C.13 manuscript in this issue are from the translation by Reinier Van Noort and Jan Schäfer.

***All of the quotes from Ridolfo Capoferro’s book in this issue are from the Swanger-Wilson translation.

***All of the quotes from Salvatore Fabris’ books in this issue are from Tom Leoni’s translation.

The first two actions

The full longest lunge starts from Capoferro’s terza guard. We break it down into three actions, or you might think of it as done in four stages.

In stage one, you have gained the opponent and are in Capoferro’s terza (or technically, a counter-posture as described in the previous series).

Action 1) - Extend the arm

Your first action in a lunge is to raise/extend the sword arm.3 Extend it out at about shoulder-height, but don’t lock the elbow. As you extend, turn the true edge of your blade toward your opponent’s blade (or where the imaginary blade would be, if you’re drilling solo). In this second stage your hand is usually in one of Fabris’ bastard hand positions.4

Action 2) - Hinge at the hips

The second action is to hinge forward at the hips while keeping your legs still. Your legs, or your platform, stays still, though you will likely push your hips/butt back a little as you hinge (see my post on Fabris’ postures to learn more about the benefits of hinging like this).

When you hinge forward, you are bringing your eyes down toward being level with your blade. So in stage three, you will be looking somewhat down your blade, which also means you’ll start putting your hilt and sword arm in a position to protect your head.5

Stage three is an offensive posture

Notice that here in stage three you have transitioned into one of the more threatening offensive postures I talked about in the series on, well, postures. Transitioning from terza - which you use to enter measure safely - to an offensive posture IS the first two actions of the lunge. Practicing the sequence of extend the arm, then hinge helps you in your transitions from terza to seconda or quarta, and at the same time helps you practice the first two actions in the lunge.

Firm-footed lunge

Action 3) - Bend the front knee/straighten the rear leg

The third action in a firm-footed lunge - a lunge where the lead foot stays put6 - is to simultaneously straighten the rear leg and bend the front knee (while also maintaining control over their sword - don’t leave that part out!). This moves your torso and hips forward to the terminal part of the lunge.

The rear leg is simply extending. Remember that you are on the balls of your feet in stance. So from terza you simply apply pressure - e.g. push - with the rear foot and straighten that leg. You should not be pressing with the heel or the side of your foot. You also shouldn’t roll your rear foot sideways at the end of your lunge.

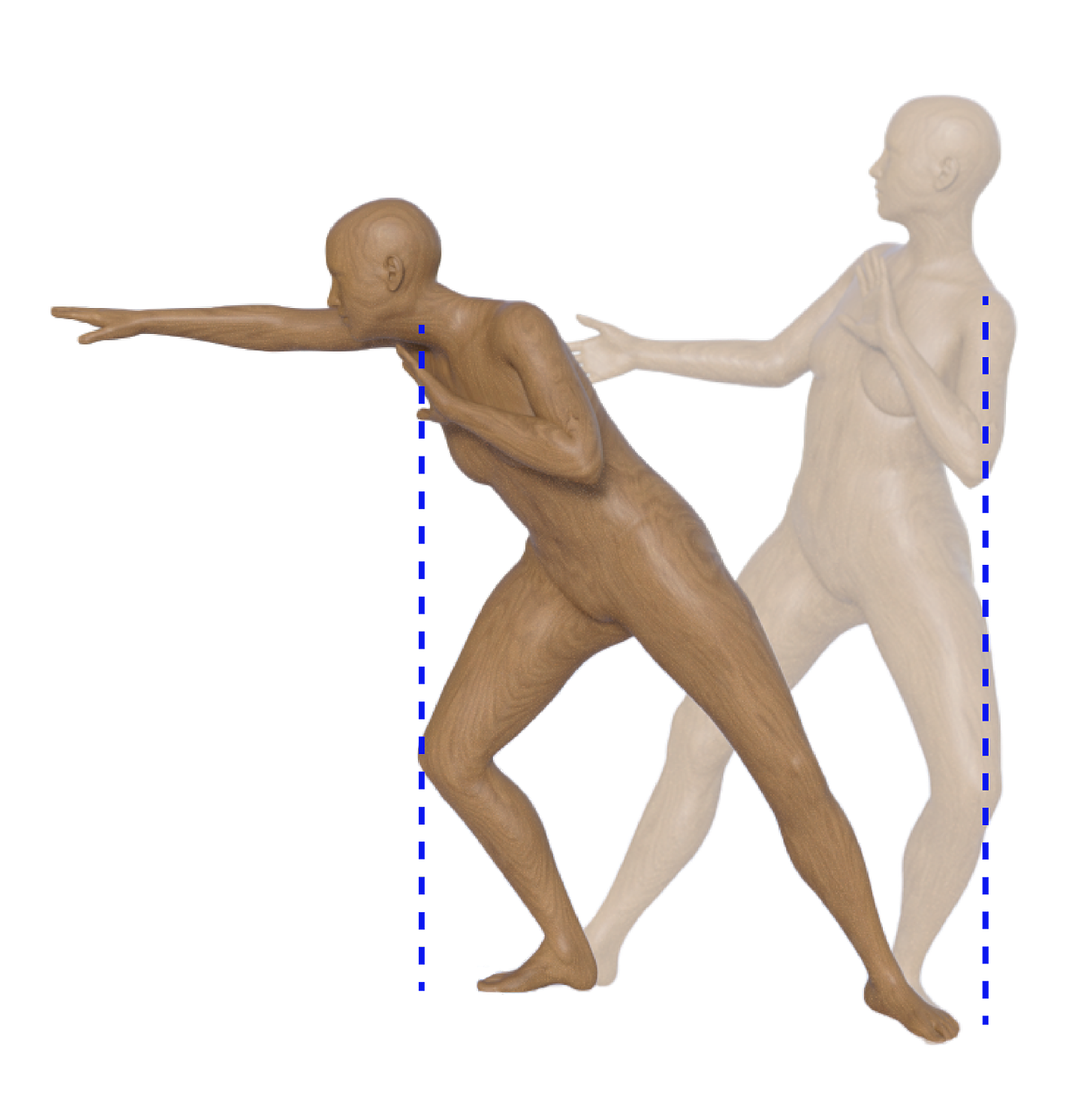

Your front knee bends and acts as a spring, catching/accepting the weight of your body as it moves forward.7 Your knee bends over and in line with your toe, just like your rear leg did in the back-weighted terza.8 Your lead foot should end up under your lead hip, not under the middle of your body. The dotted line in the image below shows the shoulder stacked over the hip, which is stacked over the knee, which is over the foot - all in a line.

If you notice, in stage four you’ve now reversed your leg positions from terza. The rear leg is now extended, and the front leg is now the ‘spring’ that catches the bodyweight.

Oh, also here in stage four is when you’re running your sword through the opponent, assuming it all went to plan.

Controlled attack

You may extend the rear leg quickly and forcefully, but note that the more forcefully you do so, the more likely you will need to take a step to catch your accelerated weight. This then becomes an extraordinary pace,9 or a stepping lunge, which we’ll discuss more in part 2.

When I want to do a firm-footed lunge, I don’t put a lot of power into the rear leg extension. It’s more like I’m reaching out quickly and powerfully, rather than explosively propelling my whole body forward. The author of the c.13 manuscript even described lunging as “falling forward” with your body.10 If I’ve gained the opponent’s blade and I’m controlling the space between us, then I’ve less need to be super explosive in my lunge. I just maintain that domination11 of their blade as I lunge, driving their point offline.

Also, note that I am not punching or jabbing with my arm. My arm is already extended as my body is propelled forward. This increases the control of my point and allows me to readjust my targeting even as I’m moving forward.

The structure

The left shoulder while standing in terza (marked A in Capoferro’s diagram above) is on the same vertical line as the left knee (B) and the left foot (C). At the end of the ideal lunge, however, the right shoulder ends over or just past the right knee (I) which is over or just past the right foot (K).12

In other words, as I illustrate below, in terza the non-dominant shoulder is over the knee which is over the foot, all in line; and at the end of the lunge the sword shoulder is over THAT knee which is over THAT foot, all in a line.

To be continued…

If you’ve read this far, you’ll note that there’s a lot more to lunging at your opponent than just throwing your sword and/or weight forward. In part 2 we’ll look at the “extraordinary pace” lunge and dig more into some of the nuances of the lunge and lunge mechanics.

Next up:

Northern Italian Postures, Part 7: The postures of the MS Dresden C.13 manuscript and Conclusions (Paid subscribers)

The lunge and its mechanics - part 2 (All subscribers)

“Lunge.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/lunge. Accessed 4 Jul. 2023.

Leoni, Tommaso. 2005. ART of DUELING: Salvator Fabris ’ Rapier Fencing Treatise of 1606. 1st ed. Chivalry Bookshelf. Page 22. (“If you want to develop reach, you should accompany your lunge with a forward bending of the body, and then withdraw it back to safety. This is a technique which requires a good deal of practice: but when you master it, you will find it quite advantageous, because it will make your body agile, your feet nimble and it will give you a good sense of distance, besides helping you deliver longer-than-average thrusts.”)

Giganti, Nicoletto. 1606. Scola, Overo Teatro. Page 4. Translated by Jeff Vansteenkiste. (“After getting in guard, first extend the arm, then extend the body forward...”)

Leoni, ART of DUELING, Page 2. (“…between the first and the second guard there is a mid-point where the hand could stop; similarly, there is one between the second and the third and between the third and the fourth. So, we could say that there are four "legitimate" guards and three "bastard" ones, the latter sharing some of the qualIties of the two guards between which they are formed.”)

Ridolfo Capoferro. 1610. Gran Simulacro Dell’arte E Dell’uso Della Scherma. Translated by Jerek Swanger and William Wilson. Page 14. (“In striking, care will be taken that the head will be somewhat more to one side than to the other, according to whether one will strike to the inside or the outside, so that it will be covered by the hilt and the sword arm.”)

Note that For Fabris, a “firm footed lunge” can also mean the rear foot stays put while the front foot makes a quick step forward and back again. Leoni, ART of DUELING, Page 22. (“A firm-footed attack is performed either by lunging forward with the right foot and withdrawing it immediately afterwards, or by just bending the body forward without any movement of the foot.”). also see Johann Georg Pascha. 2018. Proper Description of Thrust-Fencing with the Single Rapier. Translated by Reinier van Noort and Jan Schafer. Fallen Rook Publishing. Pages 41-42. (“Thrusting firm-footed is when you stay firm with your left foot, and bring the thrust in with your right, and immediately elude the danger of the enemy again.”)

Ridolfo Capoferro. 1610. Gran Simulacro Dell’arte E Dell’uso Della Scherma. Page 19. (“...which left leg during the launching throws the body and the thigh forward onto the right leg, which in exchange forms a pillar and buttress, sustaining all of the weight of the body, pushed forward to launch the blow.”)

Capoferro, Gran Simulacro Dell’arte E Dell’uso Della Scherma, Page 20. (“The ordinary [pace] is that in which one rests in guard and seeks the narrow measure. And the extraordinary is that into which one moves, lengthening the pace forward to strike.”)

Johann Georg Pascha. 2018. Proper Description of Thrust-Fencing with the Single Rapier. Translated by Reinier van Noort and Jan Schafer. Fallen Rook Publishing. Page 40. (“In the thrust you shall also extend your arm first, and after that fall forwards with your body in one tempo…”)

Capoferro, Gran Simulacro Dell’arte E Dell’uso Della Scherma, Page 39. (“One dominates the sword in two manners: in the first, when having acquired the adversary’s sword, I never quit the domination while striking.”)

Ibid. Page 20. (“In striking, the knee of the right leg is bent as far as it can be, so that the calf and the thigh come to make the most acute angle; and on the contrary, the left calf with its thigh is extended forward in an oblique line in the manner of a slope.”)